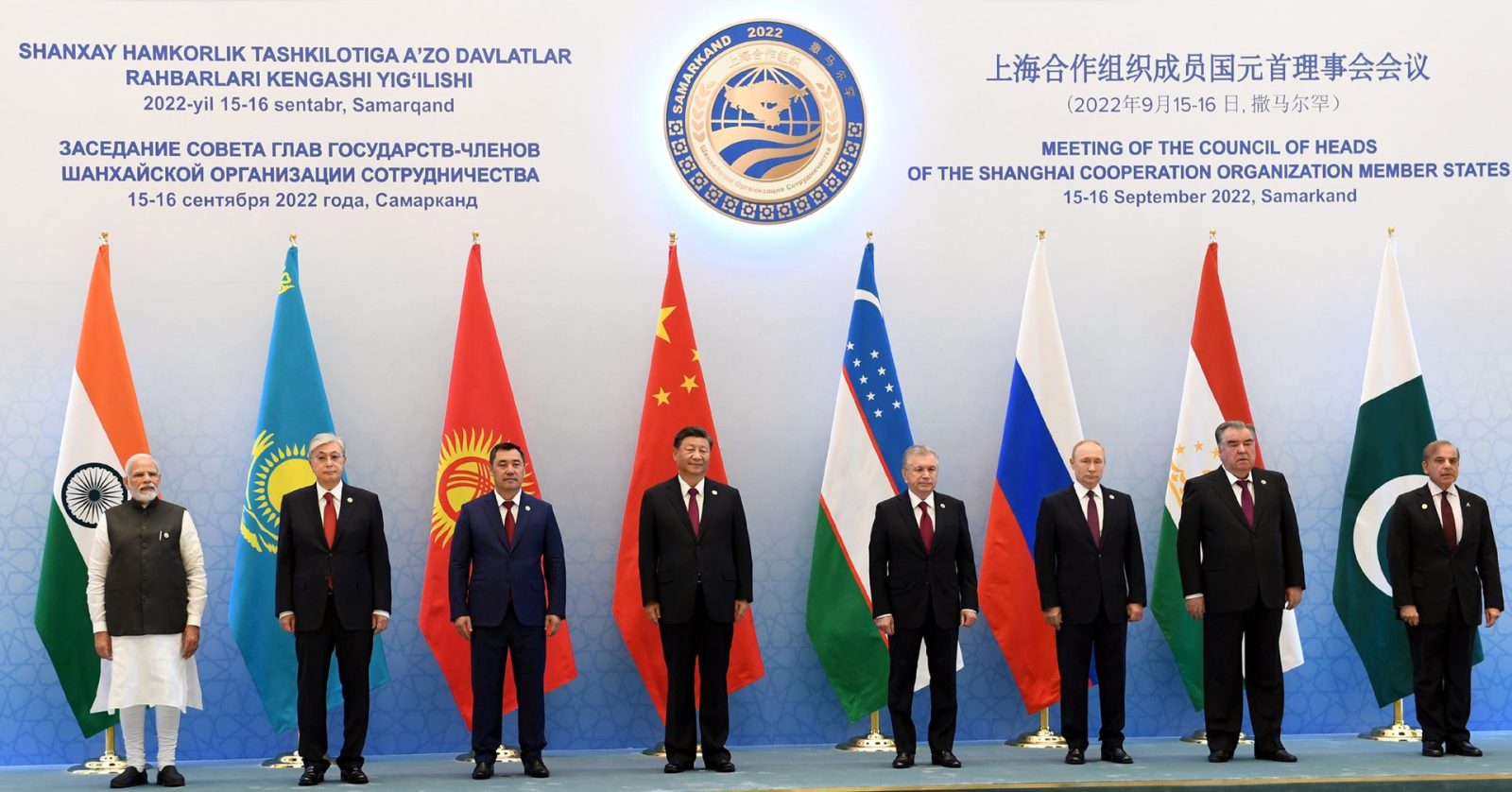

China’s SCO Diplomacy: Creating A Parallel World Order?

China is expanding its multilateral diplomacy, and one of its targets is Central and South Asia. Indeed, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is clearly in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s sights, given that many Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects are situated in SCO member countries. Before Xi attended the G20 in Bali in November 2022, the SCO was the first overseas forum that Xi attended after avoiding travelling abroad since the outbreak of COVID-19.

As a political, economic and security organisation, the SCO could be a useful instrument for China to promote an alternative to the western-led international order. The entry of Iran into the SCO has the potential to enhance the strategic value of the organisation. But the lack of cohesion among SCO member countries would hold back China’s efforts to use the SCO to pose a serious challenge to the extant international order.

The Value of SCO to China’s Foreign Policy

The SCO held its 22nd Meeting of the Council of Heads of State in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, from 15 to 16 September 2022. Xi’s re-emergence at the meeting demonstrates his intention to leverage the SCO to mark his return to the international arena in a big way.

During his speech at the meeting, Xi highlighted the need to uphold multilateralism by expounding on the importance of “safeguarding the [United Nations]-centred international system and the international order based on international law”. He also called for the rejection of “zero-sum game and bloc politics” as an admonishment of the United States and its coalition of allies and partners for destabilising the international order. In turn, he touted his Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative as potential stabilisers. More tellingly, in his bilateral meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin on the side-lines of the Summit, Xi reportedly stated: “In the face of changes of the world, of our times and of history, China will work with Russia to fulfil their responsibilities as major countries and play a leading role in injecting stability into a world of change and disorder.”

Xi clearly views the current international order as unfair and shaped by rules and norms determined by the United States and other western powers.. His speeches in state-controlled Chinese media have hinted at his ambition to create an alternative or parallel international order that is China-centric. Fairness in this alternative order lies in its envisaged purpose of helping China manoeuvre away from the constantly escalating US economic and technological sanctions.

The SCO is one of the primary diplomatic vehicles for Xi to reach his ambition. The fact that that the SCO consists of countries either unfriendly to or unaligned with the United States offers Xi a ready audience. Their adoption of the Samarkand Declaration, which called for commitment to the rules-based order and rejection of bloc politics, suggests their amenability for an alternative cooperative institution to hedge against the western-led international order.

But worryingly, if the SCO’s non-legally binding agreements are any indication, an alternative international order is likely to be one that is less rules-based, lacking in practical dispute settlement mechanisms, and where states do not have an equal voice.

Growing Significance of SCO and China’s Ambitions

As a founding member of the SCO, China is already an influential voice in the organisation. More importantly, the organisation’s growing agenda and participation (members, dialogue partners and observers) have added to its geopolitical significance, which in turn could support China’s growing ambitions.

On the agenda, there lies a putative nexus between the SCO and BRI. China sees the SCO (with the exception of India) as a natural partner of the BRI in which investments in Central and South Asian member countries could generate significant economic and diplomatic dividends for both sides. After all, this is the region where the Silk Road of the past linked China to Europe and the Middle East. For countries in the region, they stand to gain diplomatically in part by having a veto-wielding China in the United Nations and who can help them resist western pressures over democratic backsliding and human rights issues.

On participation, Iran’s ascension to permanent SCO membership in 2023 could boost the organisation’s non-western image and credibility. As a middle power that sits at the crossroads of Central Asia and the Middle East, Iran’s membership could enhance the SCO’s global heft. If SCO membership could somehow reduce the impact of Iran’s economic isolation from the west and enable it to appear less as a pariah state and engage with regional friends and rivals alike, more illiberal and autocratic states may see value in participating. These could draw them closer to China’s influence.

If the SCO could facilitate arms sales between China, Russia, and Iran, this would further upset the balance of power that western powers have shaped through arms control, much to China’s benefit. The corollary to this is that the SCO could be an avenue for these three powers to share knowledge and perhaps even gain access to emerging technologies in the field of lethal autonomous weapon systems without the need to abide by norms that the United Nations and western powers are developing.

Again, this could play well into Beijing’s hand. China sees the extant international order as constraining its mounting influence and power, and even undermining its national interests. Should the SCO’s appeal broaden with the joining of Iran, China’s geopolitical clout through the SCO would improve significantly.

No Cohesion, No Bite

Beyond a broad appeal, however, the SCO still lacks the vital cohesion found in better structured multilateral organisations such as the EU and NATO. Thus, it may still struggle to translate its growing agenda and participation into tangible cooperative outcomes for its members and offer a viable alternative international order.

This lack of cohesion was evident in the approach towards the violent border clashes between two SCO members – Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – that occurred while the Samarkand summit was ongoing. Both the presidents of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan met on the side-lines of the meeting, but clashes escalated rather than abated. It was only on 20 September that a peace deal was signed, outside the confines of the SCO.

More fundamentally, India—which has longstanding territorial spats with China, and has refrained from endorsing the BRI at SCO meetings—will assume the rotating presidency in 2023. India may well use its prerogative as president to promote an agenda that flies against China’s interests and side-lines Pakistan. Even if China attempts to isolate India within the SCO, such actions in and of themselves would break the unity of the SCO.

Future prospects of the SCO

Given that China is often preoccupied with defending itself from western criticisms at the United Nations, the SCO is one of the best non-western multilateral platforms where China could engage with other and like-minded countries from a position of respect. This position enables China to convene a parallel international community that could challenge the western-led international order. The influence of the SCO—as well as Beijing—would only continue to rise as the number of members, observers and dialogue partners grows.

But the lack of cohesion would leave China hard pressed to engender a united front among SCO members including in coordinating national positions before voting on any issue at the United Nations. One thing for certain is that the growing significance of the SCO is still miles behind the cooperative momentum of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU) and the United States’ coalition of allies and partners that were energised by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nonetheless, a bifurcated international order would add more instability to the world and the world ought to be paying more attention to the SCO.

Authors

-

Henrick Tsjeng is Associate Research Fellow with the Regional Security Architecture Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.

View all posts -

Muhammad Faizal is Research Fellow, with the Regional Security Architecture Programme, Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He completed his Master of Science in Strategic Studies at RSIS, specialising in terrorism studies. Prior to joining RSIS, Faizal served with the Singapore Ministry of Home Affairs where he was a Deputy Director

View all posts

Henrick Tsjeng is Associate Research Fellow with the Regional Security Architecture Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.