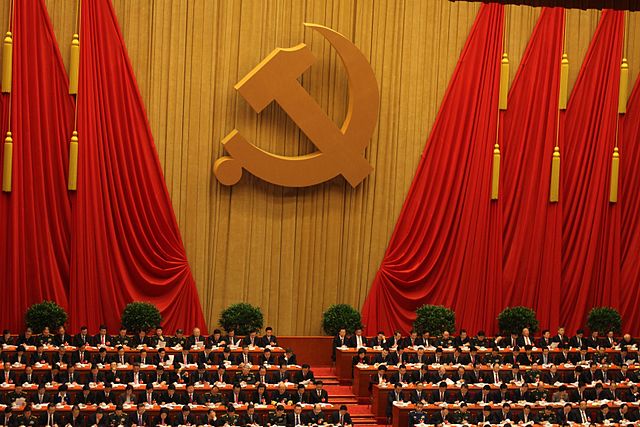

China and US in diplomatic tussle

It has become a cliché and a platitude for political observers to comment that ‘China-US rivalry has intensified’. What does this intensification really mean? US-China relations wasn’t exactly warm during the Obama years – the 44th President of the United States coined the term ‘to do a Hu Jintao’ to indicate how the former Chinese president relentlessly stuck to, and regurgitated pre-prepared talking points. He also called China a ‘free rider’. It was also during his administration that the ‘pivot to Asia’ (subsequently renamed ‘rebalance to Asia’) strategy was articulated. Beijing, in turn, as this as a containment strategy.

Nevertheless, there seems to be something qualitatively different in the US-China rivalry today, as Washington and China seems to be butting heads in every domain conceivable. Even the Covid-19 pandemic was not spared of this skirmish with both sides lobbing conspiracies and accusations. More seriously, US has accused China of hacking defence contractors and local companies to steal Covid-19 vaccine related research. As pointed out before, the pandemic should have been the perfect opportunity for both powers to cooperate, but alas, we are seeing the complete reverse of that.

Of greater concern is the de-sanitization of public discourse between these two powers. The increasingly strident, aggressive and even battle-like words, previously the sole remit of specific individuals in both countries, are now creeping into official discourse and is rapidly being normalized. Courtesies have been replaced by controversies. Politeness has been beaten down by belligerence. Casting aspersions and raising suspicions is the norm, supplanting mutual cooperation and understanding.

IR scholars have long studied the effects of narratives and discourse on foreign policy practices to show how narratives shape foreign policy outcomes. It is attractive (but dangerous) to think that the escalating war of words will have little impact on actual conflict. The risk is that is ever-present is that adverse discursive environments create precisely the sort of fertile conditions that could lead to an actual conflict. In that vein, the U.S decision to shutter the Chinese consulate in Houston and the subsequent closure of the U.S consulate in Chengdu (and the inevitable war of words that followed) adds to the debilitating situation both powers find themselves in. The decision to close the Chengdu consulate, as opposed to say the ‘lower hanging fruit’ of Wuhan or even Guangzhou is a significant step, and shows how China is prepared to struggle with the U.S.

(The Chengdu Consulate is important to Washington because it allows them to access and monitor the situation in Xinjiang and Tibet – areas and domains that the U.S. are concerned with. Of course, any closure of Consulates represents a blow but not all Consulates are created equal).

The diplomatic wrangling here is a small microcosm of the overall U.S.-China relationship. One struggles to think of any field that U.S and China can cooperate meaningfully in. North Korea used to be one such issue-area but that seems to have been thrown out of the window. Obama’s extraction of a promise from Xi not to endorse state-sponsored hacks against U.S private companies also seems to have been aborted. Educational exchanges between the two countries have been politicized and interrupted owing visa issues and the degradation of public opinions towards each other.

In any event, while it may be trite to say that the relationship between U.S and China has deteriorated and rivalry has intensified, it bears repeating this trope because the consequences of this fallout is both wide-ranging and severe, and it poses important geopolitical questions for states around the word.

Dylan is the founding editor of The Politburo and is an Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University. Views expressed are his own and do not represent the views of his employer.