China’s Multilateral Diplomacy: Not Quite a Beijing-Moscow Alliance

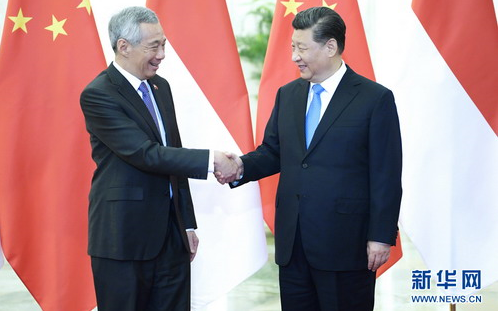

Ever since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, China’s outreach to Russia has strengthened just as Moscow’s relations with the West has nosedived. Chinese President Xi Jinping met Russian leader Vladimir Putin in March this year, following up with a meeting with Russian Federation Council Speaker Valentina Matviyenko in Beijing in July. These have fuelled concerns by observers that an anti-Western Sino-Russian alliance is being formed.

However, this characterisation may not be completely accurate. China prefers not to be entangled with alliances, but instead focuses on a multilateral approach of building loose coalitions of like-minded states and developing alternatives to the Western-led international order. Indeed, China’s key motive is not simply to promote greater global integration for its own sake, but rather to counter US influence and secure global Chinese interests.

Russia: Close partner but not formal ally

China clearly sees Russia as a major strategic partner, given both their deteriorating relationships with the United States in particular, and the West more generally. China-Russia relations also show substantive development. In terms of economic ties, trade between the two countries rose around 29 per cent between 2021 and 2022, bolstered mainly by Chinese purchases of Russia’s energy products.

More crucially, military-to-military ties between the two have also been strengthened. In July 2023, China and Russia held joint military sea and air exercises in the Sea of Japan, quickly followed by joint naval patrols in the Bering Sea not far from Alaska, signalling their ever-strengthening relationship to the United States and its Asian allies, namely Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines. These follow the largest number of joint China-Russia exercises held in 2022 based on data going back twenty years, as well as joint China-Iran-Russia naval exercises in March 2023.

However, in contrast to the United States, China eschews formal alliances in the same vein as Washington’s “hub-and-spokes” system of alliances, as Beijing has no desire to be “entrapped” by treaty alliances which would necessitate its coming to the defence of any ally that is attacked. This explains why China is wary of becoming too closely involved with Russia’s foreign entanglements, particularly the Russia-Ukraine war. Indeed, Putin acknowledged that Xi had “questions and concerns” over the war in Ukraine after the two met on the sidelines of a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Uzbekistan in September 2022.

China’s multilateral push

Instead, China has made diplomatic investments in multilateral organisations in which it has greater influence, as well as with other like-minded countries, as a way of ensuring it does not become over-dependent on its relationship with any one country, Russia included. As such, Beijing has developed and promoted its own initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), the Global Security Initiative (GSI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI).

With its strategic rivalry with the United States continuing to intensify, Beijing’s multilateral diplomacy is increasingly aimed at countering US influence globally. As such, China has sought to form a loose coalition of like-minded countries, and also to provide alternative institutions to the Western-led international order, without triggering any major conflict with the United States or its allies.

Key to this approach is China’s self-promotion as a ‘responsible major power’. This is clear from the way Beijing tends to focus on the benign aspects of its multilateral diplomacy, using feel-good concepts such as “community with a shared future for mankind”, “win-win cooperation” and “new type of international relations”, and how it embraces countries targeted by Western sanctions, like Iran. China often contrasts its concepts to what it sees as Washington’s hegemonic and bullying behaviour.

China’s words are also backed by deeds, as seen in Beijing’s brokering of the normalisation of ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as its support for peace talks between Russia and Ukraine that have nonetheless been met with scepticism. China has also made significant contributions to multilateral organisations and regions in which it has relatively more influence, as seen in the SCO, as well as the Mekong subregion in Southeast Asia.

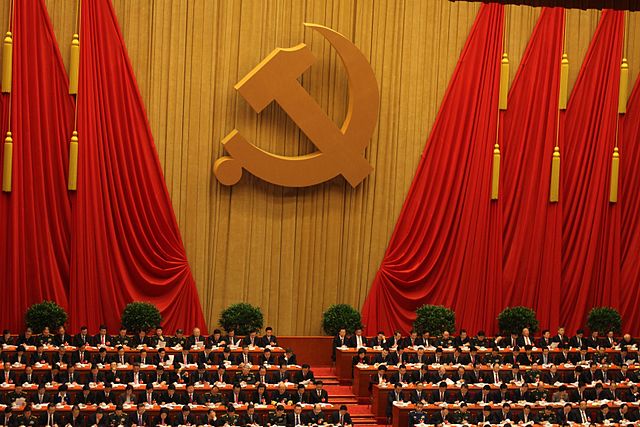

The SCO: Pushing an alternative to the Western-led order

In Central Asia, which is of significant geostrategic importance to China given its proximity, the SCO represents China’s attempt at steering a major multilateral organisation as an alternative to the Western-led rules-based order. During a speech at the recent 23rd Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the SCO, Xi reiterated talking points characteristic of China’s foreign policy, emphasising that “the notion that mankind … are increasingly becoming a community with a shared future in which everyone’s interest is closely interlinked.” Xi also highlighted that “SCO member states have upheld international fairness and justice, and opposed hegemonic, high-handed, and bullying acts.”

Similar rhetoric was present in the New Delhi Declaration, the SCO meeting’s joint statement. Crucially, the New Delhi Declaration criticised unilateral “economic sanctions other than those approved by the UN Security Council” as “incompatible with the principles of international law”. Most of all, almost all SCO members endorsed China’s BRI, amply demonstrating Beijing’s clout over the SCO. Even so, India—the sole SCO member with major disputes with China—broke ranks with the other SCO members and refused to support the BRI. Indeed, India remains the sole dissenting voice against Chinese dominance in the SCO.

Now, with Iran having joined the SCO in 2023 and Belarus set to join the following year, the organisation’s enlarged membership and heft are making it look like a viable vehicle for both Beijing and Moscow to counter the Western-led order and its institutions—particularly the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union—as well as provide an alternative institution for like-minded countries and a diplomatic lifeline for those under Western sanctions. It nonetheless would have to confront the problem of a lack of cohesion, especially given India’s membership.

Mekong subregion: An integral part of China’s approach

In Southeast Asia, which is also of geostrategic significance, Beijing’s multilateral approach can also be seen clearly. China has been hard at work implementing the BRI in the region, and these efforts have borne fruit in the form of stronger partnerships with certain Southeast Asian countries, largely in the Mekong subregion.

The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) is another example, which China—as the permanent co-chair of the mechanism—could use as a counterweight against Western-supported institutions in the subregion, such as the Mekong River Commission and the Mekong-US Partnership. China has also advocated the formation of a “pilot zone” over the Mekong subregion in its GSI concept paper, though details remain scant. Beijing has also used similar rhetoric such as “shared river, shared future”. Yet, China goes out of its way to insist that it is not forming any explicit military alliances in the region against any party, as seen in its denials against allegations that its navy would have exclusive access to Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base.

Geopolitical implications of China’s multilateral aims

China’s multilateral push has been well underway for years, particularly after Xi’s ascendancy as President of China. With the convergence of Chinese and Russian national interests, both countries are now largely acting in concert. However, China is wary of becoming too dependent on or close to Russia, and therefore also invests heavily in forming a loose coalition of like-minded states.

This will present a challenge to United States and its allies, since Beijing is providing alternatives to countries that have “fallen afoul” of the international order, the clearest examples being Russia and Iran. It would also secure Chinese interests closer to home in Central and Southeast Asia, as a counterweight to the perceived encirclement by Washington and its allies in Tokyo, Seoul, and Manila. Nonetheless, should China’s ambitions be left unchecked, they could split the region between those closer to China—especially in the Mekong subregion—and those that are more neutral or closer to the West.

Henrick Tsjeng is Associate Research Fellow with the Regional Security Architecture Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.