Is China to blame for the crisis in Sri Lanka? Not Quite

Sri Lanka is facing its biggest economic crisis since independence, which hints at the gravity of the situation, given that the country has gone through a 30 years old conflict with the LTTE and two insurrections by led by the JVP.

There is an influential section of the foreign policy establishment, in the East and the West, who are blaming China for the Sri Lankan economic meltdown.

The argument generally goes like this: China was extremely close to the Rajapaksa family, who took unsustainable loans from China and that it was this debt that led to the current crisis. This line of argument falls nicely into the narrative that China is trying to ‘trap’ Sri Lanka with debt.

This article looks at the twin claims that Sri Lanka is a victim of a Chinese debt trap, and that China has a special relationship with the Rajapaksas.

Chinese Debt Trap

In the last few years, there has been a concerted effort to show that Chinese loans to be the biggest portion of Sri Lankan debt. Despite best efforts by foreign and local economists to prove otherwise, the myth of Chinese debt trap continues.

The root cause of Sri Lanka’s current economic, and political crisis is its persistent balance of payment issues. In fact, the country has been facing balance of payment issues from the 1950s, which has been exacerbated since 1977. The gap between exports and imports have been growing, and Sri Lanka has been bridging the gap through dollars earned from borrowings, tourism and remittances from foreign workers.

China is indeed Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral creditor and thus it will and has to play a big role in Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring process, however, International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) accounted for 36.5% of total foreign debt and ISB repayments accounted for 47% of total foreign debt repayments by the end of 2021. Thus, even if China wrote off all its debt, Sri Lanka will still be saddled with debt amounts that it cannot pay back.

This is alarming given that Sri Lanka started borrowing from international capital markets only since 2007. With increasing borrowings from the capital markets country’s export-to-GDP ratio has declined by as much 50% between 2000 and 2017, from 39 percent to 21. Foreign debt servicing-to-exports ratio too has remained above 20 percent since 2011. These are clear and early indications that the country’s debt was unsustainable.

After being elected in 2019, President Rajapaksa reduced taxes, which led to rating agencies downgrading Sri Lanka’s sovereign credit ratings. This made it harder for Sri Lanka to borrow from international capital markets.

Moreover, in 2020, the pandemic crushed earnings from tourism and remittances. Some economists warned that Sri Lanka might not be able to repay its foreign debt and urged the government to go before the IMF from 2020. Others urged the President to ramp up industrialization and to promote strategic industries but the government ignored both proposals.

Energy sovereignty and food sovereignty

Sri Lanka, like many countries in the Global South, lacks in both energy and food security. The country spends almost $1.2 billion US dollars a year to run its thermal power plants. It also spends around $300 million dollars (is this USD?) annually for its coal power plants.

Successive governments have ignored calls made by energy experts to invest in renewable energy. This is mainly due to the fossil fuel industry that greases the palms of politicians, and bureaucrats. Until the current economic crisis made it impossible to purchase diesel and/or furnace oil for thermal power plants; the government paid little attention to promoting renewable energy despite a promise made in 2019 by Gotabaya Rajapaksa to drastically increase the portion of renewables in the country’s energy mix.

While Sri Lanka has been ‘self-sufficient’ in agriculture, it imports large quantities of agricultural inputs from other countries. Gotabaya Rajapaksa had come into power in 2019 promising free fertilizer for farmers, although his manifesto had called for green agriculture, spanning over the course of a decade. In 2021, it was estimated 400 million US dollars was needed to import fertilizer for the year. Given that it was impossible to allocate such a large sum of money, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration decided to ban agrochemicals overnight, destroying agricultural output, especially rice, in the middle of global food crisis.

Thus, the current implosion was due to a series of bad judgements, mismanagement, and corruption, which reaches far beyond Chinese loans, that led to the current moment in Sri Lanka’s history.

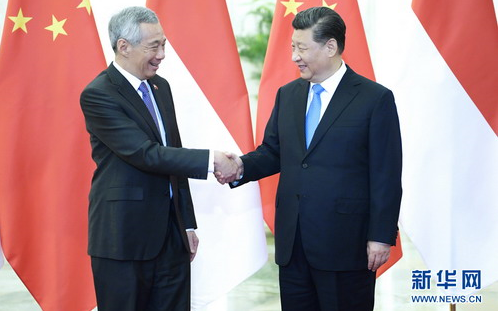

China’s special relationship with the Rajapaksas

China has always enjoyed a good relationship with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) since the 1950s. The relationship with China and Sri Lanka tightened after 2009. These developments have been often constructed as a special relationship between China and the Rajapaksas.

China overcame the 2008 financial crisis relatively unscathed through its construction sector. Once it was done building infrastructure at home, it realized that it could use its excess capacity to build infrastructure in Asian and African countries.

Coincidently around the same time, the Rajapaksa government saw infrastructure development as a way to kickstart the Sri Lankan economy, which had been adversely impacted by civil war. The Rajapaksas also thought large infrastructure projects would enhance their prestige and was a great way to enrich themselves. Chinese companies operating in the periphery built whatever the Rajapaksas wanted – so long as they were paid. Thus began a spree of projects with China between 2009 and 2014.

During this time China was giving loans freely. Chinese companies had little experience in commercial lending tun the Global South and they adhered to a high risk– high volume paradigm. By the end of the second decade of the 21st century, it was obvious that China was sitting on a pile of unsustainable debt.

Indeed, recent developments in Zambia and now in Sri Lanka have shown that there is very little China can do when countries choose to default.

Of course, China saw this coming and in response, have adopted more cautious lending approaches. For example, in November 2021, addressing the triennial Forum of China-Africa Cooperation held in Senegal, President Xi Jinping said that China would cut the headline amount of money it supplies to Africa by a third. It will also focus on SMEs, green projects, and private investment flows, instead of large infrastructure projects.

This redirection from the high-volume, high-risk paradigm to one where deals are struck on their own merit, at a smaller and more manageable scale was the reality Gotabaya Rajapaksa faced but could not understand. Rajapaksa probably believed that he held a special place in President Xi Jinping’s heart.

This is what made him tell Bloomberg that China is no longer attentive to South Asian countries in financial trouble. It is also why a number of Sinophobes and Sinophiles assumed that China would come to Sri Lanka’s aid during the current economic crisis. Unfortunately, for the Rajapaksas, China had no interest in debt trapping Sri Lanka, neither does it plans to sink a few billion dollars on saving the Rajapaksa dynasty.

Rathindra Kuruwita is a journalist and a researcher from Colombo, Sri Lanka. He holds a MSc in Strategic Studies from S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU, Singapore. He was also a fellow at Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, USA, and a participant of the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) conducted by the U.S. Department of State. He writes on security and international relations to several publications and has written extensively on the Sri Lanka-China relationship.