The Difficulty of Criticising China

- Criticising China has become increasingly common in some societies and China has tried to nip these in the bud.

- Has criticism for China gone overboard? Is China too sensitive?

Is China too thin-skinned? By the accounts of many Western media (and several non-western ones too), China is increasingly sensitive to any slights — perceived or real.

‘Hypersensitive’. ‘Playing the victim card’. ‘Thin-skinned’. These are some of the charges lobbed at Beijing.

A quick foray on wild world of Twitter shows many of these sentiments:

“The sad truth is that as China rises, instead of embracing a superpower mindset and growing a thicker skin, it is becoming increasingly more sensitive to perceived slights — all while it fosters a thin-skinned, resentful nationalism among its people.” https://t.co/Xk0dsN4Rgv

— Anna Fifield (@annafifield) October 10, 2019

Or this Tweet by the National Review for one of its op-eds:

China’s Thin Skin Bruised Yet Again | https://t.co/JQUhW78jSQ via Michael Auslin pic.twitter.com/Lu8iRuhAqX

— National Review (@NRO) February 26, 2020

We see such discourse surfacing again, particularly since many parts of the world are seeking someone to blame and that ‘someone’ is often China. Truth be told, no country likes to be criticised — no international actor will take a perceived slight lightly. Nevertheless, what these critics are claiming, is that China can brook no criticism and can admit absolutely no wrong.

(I think this is not entirely true. China, for instance, has responded decisively to accusations of racism by African countries over forced testing of Africans in Guangzhou. In fact, officials have said that there were “reasonable concerns“ in that regard and promised to act. Of course, we can debate if they would have made those admissions of it were ‘hostile’ countries making those criticism).

Vox, for example, reported how China lobbied the EU hard, to moderate criticism of China’s Covid-19 management. It notes, for instance how

“Chinese diplomats managed to persuade EU officials to scrap a reference to China running a “global disinformation” campaign, and also remove reference to Beijing’s criticism of the French response to the pandemic.”

Source: Vox

The report further states that Chinese diplomats have threatened further reactions if the EU did not water down a statement on purported Chinese disinformation. According to the New York times, this worked, as the EU produced an adulterated statement.

“…the sentence about “a global disinformation campaign” had been removed. So had references to China’s criticism of France and a pro-Chinese bot network in Serbia. Other elements had been toned down. A section on state-sponsored disinformation, singling out China and Russia, had been folded into the rest of the report.”

Source: New York Times

This, indeed, fits a broader trend of Beijing increasingly utilising its diplomats to extract concessions — more often than not, with some success. As a side note, this trend also speaks to the increased power that diplomats and the Foreign Ministry wield, particularly after Xi Jinping took power.

I wrote about Chinese diplomats’ increased power in a journal article on Chinese diplomacy, (open-access) if you are interested. Abstract can be seen below:

In any case, China’s officials, diplomats and part members have, in an increasingly apparent way, adopted a more assertive posture in deflecting criticism. See Hu Zhaoming, China’s Director-General of the Bureau of Public Information and Communication, International Department as a case in point. He was making a comment in response to President Trump’s apparent advice on disinfectants and their ability to eliminate the Coronavirus.

Mr. President is right. Some people do need to be injected with #disinfectant, or at least gargle with it. That way they won't spread the virus, lies and hatred when talking.

— Hu Zhaoming 中联部发言人胡兆明 (@SpokespersonHZM) April 26, 2020

In some ways, this is easy to understand and is borne, in my view, primarily of two reasons. First, many Chinese do, genuinely, feel aggrieved at what the West (in particular America) is saying. Actions such as filing a lawsuit against China or calling the virus a ‘Chinese virus’ certainly give people more reason to believe the narrative that there can be no genuine ‘constructive criticism’ to be had from them. Second, Chinese diplomats are much more prepared to act and attack than before, because they are incentivised to do so. In that way, active defence of China is now turning offensive in nature: to attack is to defend.

(Recall Zhao Lijian who called former national security adviser — Susan Rice — “disgraceful” and “ignorant”, reportedly returned to China’s MOFA HQ with “young admirers at the ministry gathered at his office to cheer his return”, according to the Straits Times)

Diplomats have purportedly received instructions from President Xi to show fighting spirit – widely taken as a clarion call to better defend China’s image and go on the offensive. The ironic side effect of this, at least to Western observers, is that China’s image continues to slide because they are becoming more belligerent.

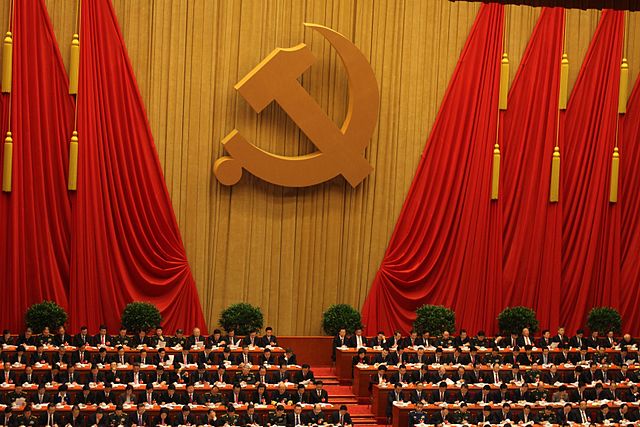

I hasten to add that criticism of China frequently conflates ‘Chinese’, ‘China’, ‘the CCP’ or ‘Chinese government’ into one big blob. These are not one and the same. But can you also distinguish between them neatly? On this, Kerry Brown has an excellent article on the problems with such compartmentalisation (i.e ‘I love the Chinese people but hate the CCP’). Give his article a read here.

Can China perhaps manage criticism better? Perhaps. Likewise, petty political moves and the self-aggrandising and self-exculpatory criticism of China is, at least, partially to blame for Chinese reactions as well. Unfortunately, as opposed to seeing greater cooperation between the two major powers in face of a global pandemic, we are seeing heightened competition. And this does not bode well for the rest of the world.

Dylan is the founding editor of The Politburo and is an Assistant Professor at Nanyang Technological University. Views expressed are his own and do not represent the views of his employer.

Interesting article, first one I’ve read on this website, would just say that you need to have fewer inserts in your text, I feel like the the large quotations break up the flow a bit too much.

Thank you for your comments. Will certainly keep that in mind your suggestions in our future commentaries!